Discover crucial spinal cord care tips for enhancing your health and wellbeing in our ultimate guide.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Brief Overview of the Spinal Cord

The spinal cord is a long, cylindrical structure composed of nervous tissue that extends from the brainstem to the lower back. It serves as the main pathway for transmitting information between the brain and the rest of the body. The spinal cord is part of the central nervous system (CNS) and plays a crucial role in relaying sensory and motor signals, as well as coordinating reflexes independently of the brain2.

Importance of the Spinal Cord in the Human Body

The spinal cord is essential for conducting impulses from the brain to the body and generating reflexes that make our daily functioning smooth. It carries nerve signals that control voluntary movements, involuntary functions like heartbeat and breathing, and sensory information such as touch, pressure, and pain2. Damage to the spinal cord can significantly impact movement, sensation, and overall bodily functions.

Purpose and Structure of the Article

This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the spinal cord, covering its anatomy, location, functions, common diseases and disorders, involved organs and systems, prevention, diagnosis, symptoms, treatment, and tests. The structure of the article is designed to offer detailed and informative content for readers seeking to understand the spinal cord in depth.

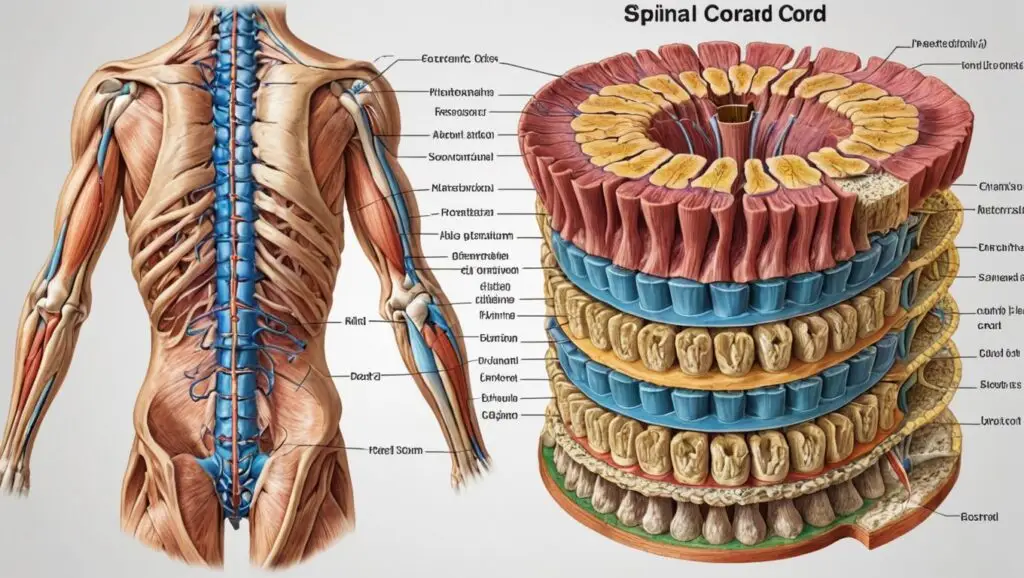

2. Anatomy of the Spinal Cord

2.1 Structure

Basic Anatomy

The spinal cord is a cylindrical structure approximately 42-45 cm long in adults, with a diameter of about 1 cm. It begins at the base of the brain, extending from the medulla oblongata at the level of the foramen magnum, and runs down to the first or second lumbar vertebra, where it tapers into a structure called the conus medullaris3.

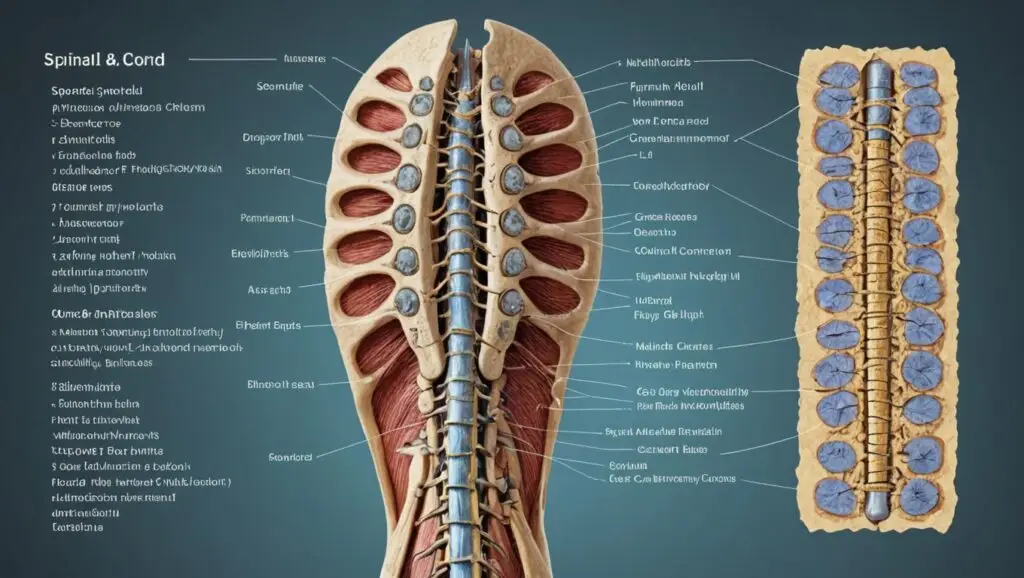

Spinal Cord Segments

The spinal cord is divided into four main regions, each corresponding to different sections of the vertebral column:

- Cervical Region: The uppermost portion, consisting of eight cervical spinal nerves (C1-C8), located within the cervical vertebrae.

- Thoracic Region: The middle portion, consisting of twelve thoracic spinal nerves (T1-T12), corresponding to the thoracic vertebrae.

- Lumbar Region: The lower-middle portion, consisting of five lumbar spinal nerves (L1-L5), within the lumbar vertebrae.

- Sacral Region: The lowest portion, consisting of five sacral spinal nerves (S1-S5), located in the sacral part of the vertebral column3.

White and Gray Matter

The spinal cord is composed of white and gray matter. The white matter consists of myelinated nerve fibers that form ascending and descending tracts, allowing communication between different parts of the CNS. The gray matter, located centrally, contains neuron cell bodies and is involved in processing and integrating information3.

Spinal Nerves and Roots

Thirty-one pairs of spinal nerves emerge from the segments of the spinal cord to innervate body structures. These nerves are divided into dorsal (sensory) and ventral (motor) roots, which join to form the spinal nerves. The spinal nerves are responsible for transmitting sensory and motor information between the spinal cord and the rest of the body3.

2.2 Layers and Protection

Meninges

The spinal cord is protected by three layers of connective tissue called meninges:

- Dura Mater: The outermost, tough layer.

- Arachnoid Mater: The middle, web-like layer.

- Pia Mater: The innermost, delicate layer that closely adheres to the surface of the spinal cord3.

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF)

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounds the spinal cord, providing cushioning and protection against mechanical injury. It also helps maintain a stable environment for the spinal cord by removing waste products and supplying nutrients3.

Vertebral Column

The spinal cord is housed within the vertebral column, which consists of 33 vertebrae stacked on top of each other. The vertebral column provides structural support and protection for the spinal cord, preventing damage from external forces3.

3. Location of the Spinal Cord

3.1 Position in the Body

Cervical Region

- The cervical region of the spinal cord is located in the neck and consists of eight cervical spinal nerves (C1-C8).

- This region is responsible for transmitting signals between the brain and the upper part of the body, including the neck, shoulders, arms, and hands.

- Injuries to the cervical region can lead to significant impairments due to its role in controlling many critical functions and movements.

Thoracic Region

- The thoracic region is located in the upper and mid-back and consists of twelve thoracic spinal nerves (T1-T12).

- It plays a crucial role in the control of the chest muscles and some abdominal muscles, as well as sensation in the back and abdomen.

- This region is less prone to injury compared to the cervical and lumbar regions due to its relative stability.

Lumbar Region

- The lumbar region is situated in the lower back and consists of five lumbar spinal nerves (L1-L5).

- It is responsible for transmitting signals to and from the lower parts of the body, including the hips, legs, and feet.

- Injuries or disorders in the lumbar region can affect mobility and sensation in the lower extremities.

Sacral Region

- The sacral region is located at the base of the spine and consists of five sacral spinal nerves (S1-S5).

- This region connects with the pelvic organs, genitals, buttocks, and parts of the legs.

- The sacral spinal cord is involved in controlling bowel, bladder, and sexual functions.

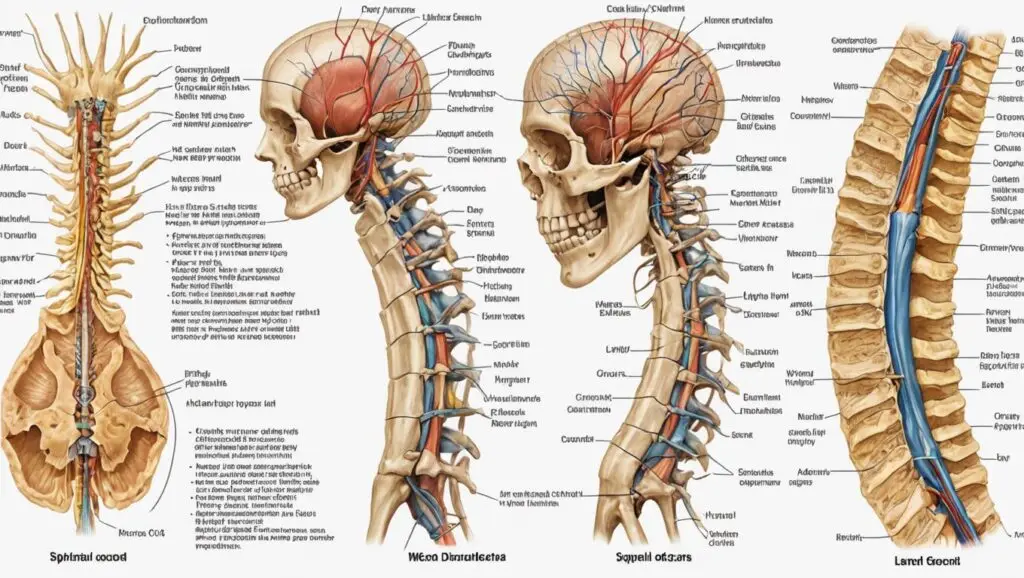

3.2 Relations with Surrounding Structures

Connection to the Brain

- The spinal cord is connected to the brain through the brainstem, specifically the medulla oblongata.

- This connection allows for the integration and coordination of motor and sensory information between the brain and the spinal cord.

Interaction with Peripheral Nerves

- The spinal cord interacts with peripheral nerves through its dorsal (sensory) and ventral (motor) roots.

- Peripheral nerves branch out from the spinal cord to innervate various parts of the body, facilitating communication between the central nervous system and peripheral tissues.

4. Functions of the Spinal Cord

4.1 Motor Functions

Voluntary Movements

- The spinal cord transmits motor commands from the brain to the muscles, enabling voluntary movements.

- Motor neurons in the spinal cord control the contraction and relaxation of skeletal muscles, allowing for precise and coordinated actions.

Reflex Actions

- The spinal cord is responsible for generating reflexes, which are automatic responses to specific stimuli.

- Reflex arcs involve sensory neurons, interneurons in the spinal cord, and motor neurons, allowing for quick responses without the need for brain input.

- Examples of reflex actions include the knee-jerk reflex and withdrawal reflex.

4.2 Sensory Functions

Transmission of Sensory Information

- The spinal cord carries sensory information from the body to the brain, allowing for the perception of touch, pressure, pain, temperature, and proprioception.

- Sensory neurons relay signals from sensory receptors to the spinal cord, where they are transmitted to the brain for processing and interpretation.

4.3 Autonomic Functions

Regulation of Involuntary Functions

- The spinal cord plays a role in regulating involuntary functions, including heart rate, blood pressure, respiration, and digestion.

- Autonomic pathways in the spinal cord connect to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, which control these vital functions.

5. Common Diseases and Disorders

5.1 Spinal Cord Injuries (SCI)

Causes and Types (Complete vs. Incomplete) Spinal cord injuries (SCI) typically result from traumatic events such as automobile accidents, falls, sports injuries, or violence. They are categorized based on how much of the spinal cord’s function remains after the injury:

- Complete Injury: All sensory and motor function is lost below the level of injury. A complete section means a total interruption in the nerve communication channel, leading to full paralysis and a loss of sensation in affected areas.

- Incomplete Injury: Some signal transmission remains intact, leading to partial loss of function. Patients may retain varying degrees of sensation or movement below the injured level, which influences recovery prospects and rehabilitation potential.

Symptoms and Effects

- Immediate Effects: Loss of movement or sensation, shock, potential respiratory difficulties (especially with a high cervical injury), and a sudden drop in blood pressure.

- Long-term Effects: Paralysis, chronic pain, spasticity, and loss of bladder or bowel control. These complications can have profound impacts on a patient’s daily life, emotional state, and independence.

Rehabilitation and Recovery Rehabilitation is typically a painstaking, long-term process that includes:

- Physical Therapy: Regaining mobility, strength, and flexibility through guided exercises.

- Occupational Therapy: Helping patients adapt to new methods of everyday functioning and using assistive devices when necessary.

- Adaptive Technologies and Counseling: Addressing both the physical and emotional challenges associated with a spinal cord injury.

- Innovative Treatments: Cutting-edge research, such as stem cell therapies, and experimental interventions aimed at enhancing neural regeneration.

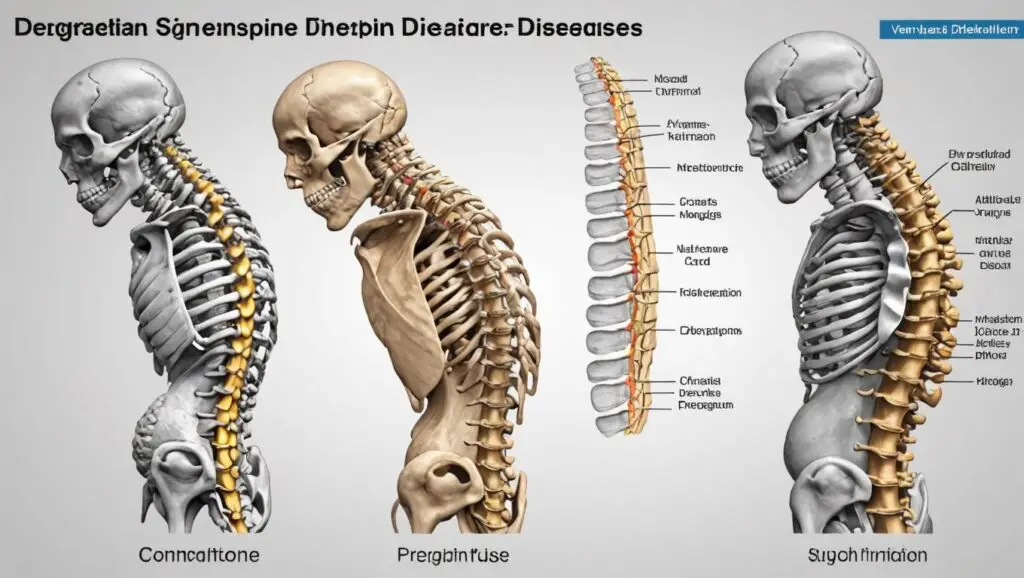

5.2 Degenerative Diseases

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

- Overview: ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord, leading to muscle weakness and loss of motor control.

- Symptoms: Progressive muscle weakness, difficulty speaking, swallowing, and eventually breathing.

- Impact: The loss of neural control undermines everyday tasks, and survival time post-diagnosis is typically limited.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

- Overview: MS is an autoimmune disorder where the body’s immune system attacks the protective myelin sheath covering nerve fibers. Although it primarily affects the central nervous system, lesions may also be found along the spinal cord.

- Symptoms: Symptoms vary widely—ranging from vision problems and muscle weakness to coordination difficulties and cognitive impairments.

- Course: Some patients experience relapsing-remitting patterns, while others have progressive forms.

Spinal Stenosis

- Overview: This condition is characterized by the narrowing of spaces within the vertebral column, which can compress the spinal cord and nerves.

- Symptoms: Pain, numbness, muscle weakness, and balance issues, particularly in the lower back and legs.

- Management: Treatment ranges from physical therapy and medications to surgery, depending on the severity of the compression.

5.3 Infections and Inflammatory Conditions

Spinal Meningitis

- Overview: Spinal meningitis is an inflammatory condition of the meninges—the protective layers surrounding the spinal cord. It is most commonly caused by infections from bacteria or viruses and can lead to serious neurological complications.

- Symptoms: Severe headache, neck stiffness, fever, and, in severe cases, altered mental status.

- Treatment: Prompt antibiotic or antiviral treatment is critical, along with supportive care in hospital settings.

Transverse Myelitis

- Overview: Transverse myelitis is characterized by inflammation across both sides of one segment of the spinal cord. This inflammation can damage myelin, interrupting signal transmission.

- Symptoms: Rapid onset of weakness, pain, sensory alterations (such as numbness or tingling), and sometimes bowel or bladder dysfunction.

- Management: High-dose corticosteroids, plasma exchange therapy, and physical rehabilitation are common treatment approaches.

5.4 Tumors and Cancers

Types and Locations

- Primary Tumors: These originate within the spinal cord itself (e.g., ependymomas, astrocytomas) and can be benign or malignant.

- Secondary (Metastatic) Tumors: More commonly, cancers from other parts of the body spread (metastasize) to the spine, including from lungs, breasts, or prostate cancer.

Symptoms and Treatment Options

- Symptoms: Localized back pain, neurological deficits such as numbness or weakness, and in some cases, loss of bowel or bladder control.

- Diagnosis: Detailed imaging studies (MRI, CT scans) and sometimes biopsy are conducted to determine tumor type and extent.

- Treatment: Options include surgical resection, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of these modalities. The prognosis depends largely on the type, location, and stage of the tumor.

6. Organs and Systems Involved

6.1 Nervous System

Central Nervous System (CNS)

- Overview: The spinal cord is a critical component of the CNS, working in tandem with the brain to process and transmit information.

- Role: It acts as a conduit for electrical signals and reflexes, coordinating targeted responses and complex functions such as movement, sensation, and cognition.

- Integration: Communication between the spinal cord and the brain is essential for both routine and rapid reflex actions.

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS)

- Overview: The PNS consists of all the nerves that branch out from the spinal cord to the rest of the body.

- Role: It carries sensory information from the external environment and organs back to the CNS, and transmits motor commands from the CNS to the muscles and glands.

- Interaction: The seamless interaction between the PNS and the spinal cord ensures that sensations are perceived and appropriate motor responses are initiated.

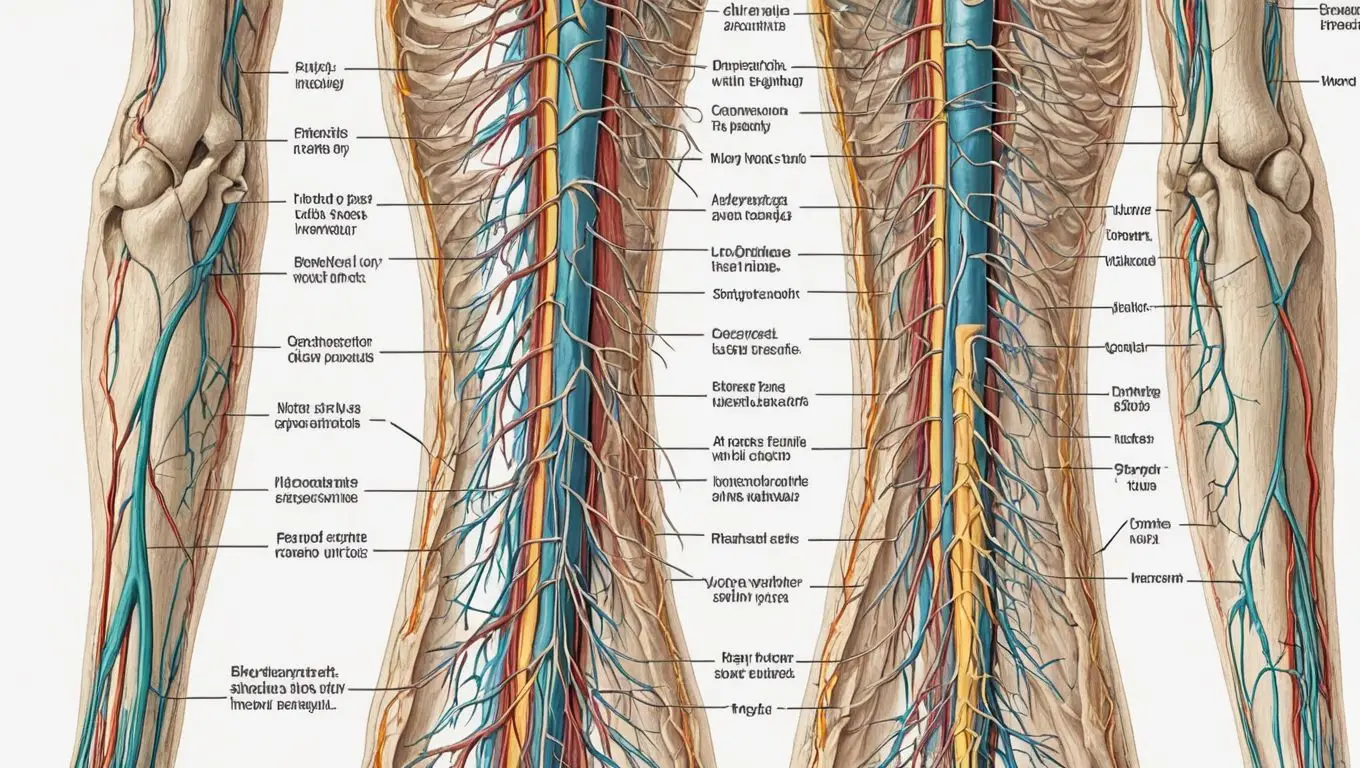

Image: Nervous System Integration

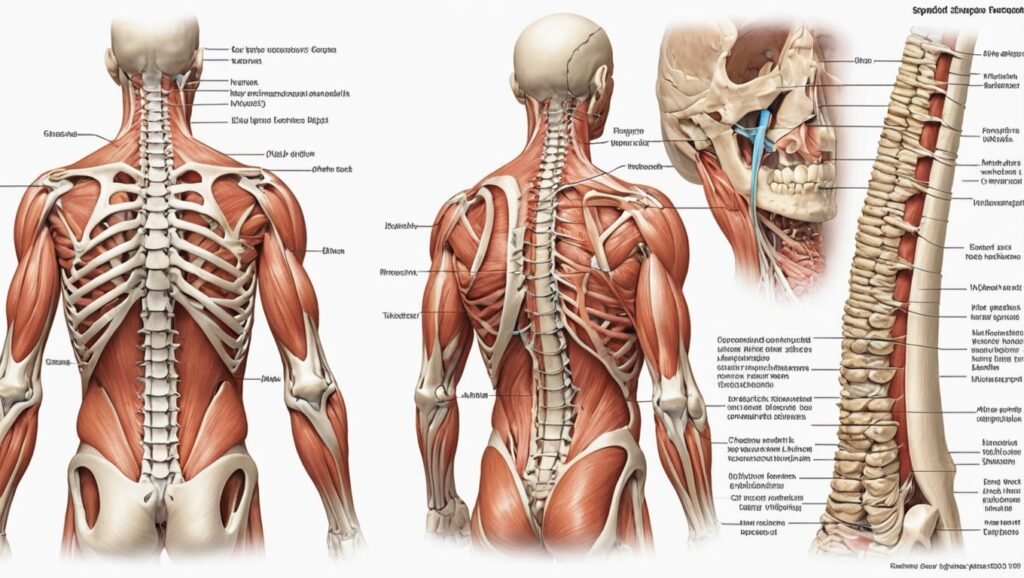

6.2 Musculoskeletal System

Interaction with Muscles and Bones

- Vertebral Column: The spinal cord runs within the protective bony canal of the vertebral column. This structure not only shields the spinal cord from everyday injury but also provides the framework for the body’s posture and movement.

- Muscular Connections: Nerve signals from the spinal cord ensure the precise contraction and relaxation of the muscles attached to the spine. These coordinated signals allow for activities ranging from simple postural adjustments to complex, dynamic movements.

- Support and Movement: Healthy interactions between the spinal cord and the musculoskeletal system are essential for mobility and overall physical stability. Damage to the spinal cord can lead to significant disruptions in muscle control, leading to weakness or spasticity.

7. Prevention of Spinal Cord Issues

7.1 Lifestyle and Health Tips

Exercise and Physical Activity Maintaining an active lifestyle is essential for a healthy spinal cord. Regular exercise improves blood circulation, enhances muscle strength, and supports the stability of the vertebral column. Recommended activities include:

- Cardiovascular Workouts: Engage in moderate activities such as walking, swimming, or cycling that improve heart function and overall stamina.

- Strength Training: Exercises targeting core muscles, including yoga, Pilates, or weight training, help stabilize and protect the spine.

- Flexibility and Balance: Stretching routines and balance exercises prevent muscle stiffness and reduce the risk of falls, which can lead to spinal injuries.

Healthy Diet and Nutrition A balanced diet is key to maintaining strong bones and a resilient nervous system. Focus on:

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Found in fish, walnut, and flaxseed, they are known to support nerve function.

- Calcium-Rich Foods: Dairy products, leafy greens, or fortified alternatives contribute to strong bones and vertebral health.

- Hydration: Adequate water intake helps keep the intervertebral discs hydrated, ensuring they function as natural shock absorbers.

7.2 Safety Measures

Injury Prevention Strategies Proactively avoiding accidents and injuries is vital for spinal protection. Key strategies include:

- Protective Gear: Wear helmets during biking, skating, or contact sports.

- Safe Lifting Techniques: When lifting heavy objects, bend your knees instead of your waist to reduce stress on your back.

- Fall Prevention: Incorporate balance exercises and home safety modifications like non-slip mats and clear walkways.

Ergonomics and Posture Proper ergonomics prevents chronic strain on your spine. Consider the following:

- Workstation Setup: Ensure your desk and chair support a neutral spine position, keeping computer screens at eye level.

- Regular Movement Breaks: Stand, stretch, and reposition yourself frequently when sitting for extended periods.

- Posture Awareness: Maintain an upright posture while walking or standing and seek ergonomic advice if you experience persistent discomfort.

8. Diagnosis and Tests

8.1 Clinical Evaluation

Medical History and Physical Examination A comprehensive diagnosis begins with a detailed clinical evaluation:

- Medical History: A complete review of past injuries, symptoms, or related conditions helps guide further testing.

- Physical Examination: A neurological exam assesses motor function, reflexes, and sensory responses. This includes testing strength, coordination, and areas of pain or numbness.

8.2 Imaging Techniques

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging): MRI is the preferred imaging method for evaluating spinal cord integrity. It delivers detailed images of soft tissues, nerve roots, and intervertebral discs without using ionizing radiation. CT Scan (Computed Tomography): CT scans provide excellent detail of bony structures, helping identify vertebral fractures or abnormalities efficiently—particularly useful in emergencies. X-ray: X-rays serve as an initial screening tool to reveal structural changes in the vertebral column. While limited in soft tissue detail, they can guide further diagnostic steps.

8.3 Laboratory Tests

Blood Tests: Blood tests check for systemic markers like inflammation, infection, or autoimmune conditions that might affect spinal health. CSF Analysis (Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis): A lumbar puncture is performed to obtain cerebrospinal fluid, which can reveal abnormalities such as increased protein levels, white blood cells, or infectious organisms causing conditions like meningitis.

9. Symptoms of Spinal Cord Problems

9.1 Common Symptoms

Pain: Back pain or neck pain is the most frequent symptom of spinal cord issues. It can be a dull ache or a sharp, debilitating sensation depending on the condition’s severity.

Numbness and Tingling: Loss of sensation in the limbs, often in a “pins and needles” pattern, can indicate nerve compression or irritation within the spinal cord.

Muscle Weakness: A noticeable decline in strength, especially in the arms or legs, may result from impaired nerve signals. This weakness can affect balance and coordination, limiting daily activities.

9.2 Severe Symptoms

Paralysis: Severe damage to the spinal cord might result in partial or total paralysis below the injury site, profoundly affecting mobility and quality of life.

Loss of Bowel and Bladder Control: Dysfunction in these autonomic areas is a critical sign of severe spinal cord damage, necessitating immediate medical attention to manage potential complications.

10. Treatment and Management

10.1 Medical Treatments

Medications: Pharmacological interventions help manage pain, reduce inflammation, and address muscle spasticity. Common medications include:

- Anti-inflammatory Drugs: NSAIDs or corticosteroids reduce swelling and alleviate pain.

- Neuropathic Pain Relievers: Specific medications can help control nerve pain.

- Other Supportive Drugs: Muscle relaxants or medications targeting spasticity may be prescribed.

Surgical Interventions: When conservative treatments fail, surgery may be required to:

- Decompress the Spinal Cord: Procedures like laminectomy or discectomy to relieve pressure.

- Stabilize the Spine: Spinal fusion or implantation of devices to support weakened vertebrae.

- Tumor Removal: Resection of benign or malignant growths impacting the spinal cord.

10.2 Rehabilitation and Therapy

Physical Therapy: A tailored rehabilitation program with physical exercise boosts recovery. Therapy focuses on:

- Restoring Strength: Targeting affected muscle groups with gradual exercises.

- Improving Mobility: Range-of-motion exercises and balance training.

- Preventing Further Injury: Teaching exercises that safeguard the spine during daily activities.

Occupational Therapy: Occupational therapy aims to enable patients to resume everyday activities by:

- Adapting the Environment: Recommendations for home or workspace modifications.

- Skill Development: Techniques for handling daily tasks more efficiently.

Psychotherapy and Counseling: Chronic spinal conditions can impact mental well-being. Counseling and psychotherapy support emotional health by:

- Addressing Anxiety and Depression: Helping patients cope with lifestyle changes.

- Strengthening Coping Mechanisms: Providing tools and strategies for managing chronic conditions.

11. Tests to be Carried Out

11.1 Diagnostic Tests

Neurological Examinations Neurological examinations are essential in identifying the extent and location of spinal cord impairment. These evaluations include:

- Motor Function Tests: Assessing strength, muscle tone, and coordination to determine whether nerve pathways are intact.

- Sensory Function Tests: Evaluating responses to touch, temperature, and pain stimuli, which helps pinpoint areas of sensory loss or enhancement.

- Reflex Testing: Checking deep tendon reflexes (e.g., knee-jerk response) to understand the integrity of spinal reflex arcs.

Image: Neurological Examination Process

Electromyography (EMG) Electromyography is used to assess the electrical activity generated by muscles. It helps in:

- Evaluating Muscle Response: Detecting abnormal muscle electrical potentials which may signal nerve damage.

- Localizing Neurological Deficits: EMG can identify issues along the peripheral nerves and the nerve roots emerging from the spinal cord.

- Guiding Treatment Decisions: The findings play a crucial role in choosing the right rehabilitative strategy or surgical intervention.

Nerve Conduction Studies Nerve conduction studies (NCS) measure the speed and strength of electrical signals conducted along nerves. These tests help to:

- Evaluate Signal Transmission: Identify any slowing or blockages in nerve signals indicative of demyelination or axonal injury.

- Distinguish Between Disorders: NCS can differentiate between peripheral neuropathies and direct spinal cord impairments.

- Complement EMG Findings: Together with EMG, NCS offers a complete picture of nerve functionality, enhancing diagnostic accuracy.

Image: Nerve Conduction Studies

11.2 Monitoring and Follow-up

Regular Check-ups Continual monitoring after an initial diagnosis is critical to track progress and adjust treatment plans. This involves:

- Scheduled Neurological Evaluations: Regular examinations to assess any changes and improvements in nerve function.

- Repeat Diagnostic Testing: Periodic imaging or electrophysiological tests to monitor the status of the spinal cord and to catch any progression of disease early.

- Patient Self-reporting: Encouraging patients to maintain diaries noting any new symptoms or changes, which can assist healthcare providers in fine-tuning therapies.

Long-term Management Strategies Managing spinal cord issues requires a proactive and adaptable approach:

- Customized Rehabilitation Programs: Personalizing therapies such as physical or occupational therapy to maintain functionality and independence over time.

- Chronic Pain Management: Using medication, alternative therapies, or behavioral interventions to alleviate persistent discomfort.

- Technology Integration: The use of assistive devices (e.g., exoskeletons or neurostimulators) and telemedicine to adapt treatment for long-term management.

- Lifestyle Adjustments: Ongoing support in ergonomic techniques, exercise, and diet modifications to reduce the risk of secondary complications.

Image: Long-term Management

12. Conclusion

Summary of Key Points

- Comprehensive Anatomy and Functionality: We’ve detailed the intricate anatomy of the spinal cord, its segmented locations, and its roles in motor, sensory, and autonomic functions.

- Common Disorders and Their Impact: The article examined traumatic injuries, degenerative diseases such as ALS and MS, infections, and tumors, shedding light on the risks and complications associated with each condition.

- Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment: From lifestyle adjustments and safety measures to advanced diagnostic tests like MRI, EMG, and nerve conduction studies, the various preventive strategies and treatments were explored.

- Patient Management: Long-term management and follow-up care are critical to coping with spinal cord disorders. Regular check-ups and ongoing rehabilitation help maximize recovery and maintain quality of life.

Importance of Awareness and Early Detection

Early detection is paramount in managing spinal cord issues before they progress to more severe conditions. An informed public and a proactive approach to health monitoring can improve treatment outcomes and minimize complications. Public education about the symptoms and risks associated with spinal cord issues is equally vital to foster prompt intervention.

Future Directions in Spinal Cord Research and Treatment

- Innovative Therapies: Emerging research into stem cell therapy, gene editing, and advanced surgical techniques holds promise for reversing or mitigating spinal cord injuries.

- Neuroplasticity and Rehabilitation: Advances in understanding neuroplasticity may lead to novel rehabilitation protocols, enabling improved recovery of function even in cases of severe damage.

- Integration of Technology: The development of wearable devices and robotics, as well as enhanced imaging modalities, is paving the way for personalized, precision-based treatment plans.

- Collaborative Research Initiatives: Global partnerships between medical research centers continue to push the frontiers of knowledge, promising more effective strategies for early diagnosis, management, and potential cures.

13. References

Credible Sources and Studies

For those interested in further study or verification, here are examples of credible sources where you can find detailed, evidence-based information on spinal cord anatomy, disorders, and treatments:

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS): Provides extensive resources and research updates on spinal cord injuries and neurological conditions. NINDS Website

- The Spinal Cord Injury Information Network (SCIN): Offers patient resources, research highlights, and clinical guidelines related to spinal injuries. SCIN Website

- Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine: Features peer-reviewed articles exploring the latest research developments in spinal cord medicine. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine

- World Health Organization (WHO): Provides global data on diseases and health guidelines that include spinal health considerations. WHO Website

- PubMed Central (PMC): An open-access repository of biomedical research articles, including studies on spinal cord pathology and treatment. PubMed Central

Additional Reading Materials

- Books on Spinal Neuroscience: Look for textbooks on spinal cord anatomy and neurophysiology available in academic libraries or online resources.

- Medical Conference Proceedings: Review the proceedings of annual neurological and spinal research conferences, which often contain the latest findings and treatment innovations.

- Patient Advocacy Groups and Blogs: Websites and blogs run by spinal cord injury advocates often offer personal insights and summaries of recent research tailored for a wider audience.

Share this content: